The Long Hua Si Buddha Temple in Shanghai hosts many treasures, including this room filled with miniature gold-colored Buddhas. There were many more than could be captured with a camera.

I remember when I was in college, one of my biggest complaints about the professors (and believe me, there were many!) was that they were not recruited based on any demonstrated ability to convey their knowledge. A corollary to this is that when the knowledge gradient between student and teacher gets large, the professors don’t know what they know. Everything that makes them an expert has been internalized, and therefore they have no clue what’s obvious and what’s not, or that something so obvious even needs explaining in the first place. Coupled with a lack of screening for effective teaching skills, one wonders how the ideals of the university actually get realized.

After I returned from Shanghai I took many steps to make sure my teacher burnout didn’t return. I worked with the vocational high school and we agreed that I would work from the textbooks they gave me. In exchange, they will supply an English-speaking Chinese teacher in my class for the first 10 minutes of each hour to make sure the assignments are clearly understood. My other school wasn’t quite so easy – I still don’t have adequate textbooks or clear goals of what they want the kids to know. But there was plenty of clear direction from the students: “Teach us how to pass the IELTS test!”

The IELTS exam is China’s standardized test for English proficiency.

Those who pass it are eligible to spend a year abroad in Australia or New Zealand to further their English skills – and keep in mind that foreign travel requests for most of China’s citizens are often rejected by a bureaucrat. Like all standardized tests, a whole industry has sprung up around how to pass the reading, writing, speaking, and listening components without fully understanding the material being presented. But those courses cost money; and my students wanted me to help them pass it for free. (Regardless, I was fascinated by the fact that it was the students who actually wanted me to teach to the test!)

Well, OK, I suppose I could do that, but it doesn’t really leverage the opportunities that a native English speaker can bring to the classroom (which is to help refine the skills of the students who already have a good foundation of the mechanics of grammar). But when I grade their papers I become panic-stricken: How in the world do I teach them how to avoid writing like this?:

Tom went to in Florida. he took many food in the car, just drove away. found some old food will spoil especially milk. He think, these food wasn’t terribly serious. So he take old food away.

Just then, he amazed visit view. Oh, my god. Very very beautiful. But, have a car crash and he’s car. He is give as a present the hospital. This hospital rather nasty and did not quite quiet. Oh, it spoilt the whole holiday. He very pity. again Just before I come back, have a car and again crashed into our car.

(Yes, this is an extreme example. And no, this student won’t make it to New Zealand.) Simply marking things wrong and handing them back won’t give them the feedback they need to improve. Marking up their papers with red ink and fixing every mistake will only take away from my sleep and doesn’t address the underlying problem of the missing foundation of grammar. Like the college professors I once despised in my youth, it seems I have internalized English grammar to the point where I don’t even know what the rules are anymore.

I am reminded of just how complex, irregular and arbitrary English is as a language. This is exacerbated by the fact that many parts of English (articles and conjugated verbs, mostly) just don’t exist in the Chinese language, so teaching what is needed is more a lesson in abstraction. For example, the phrase “What did you say?” literally translates to “You speak what?” in Mandarin. Similarly, “How much does it cost?” translates to “Much little money?” Much of the ‘glue words’ just aren’t there.

It would take years for me to teach all of the fundamentals of grammar in order for them to pass the test in December of this year (!), and I think it’s unreasonable to expect any English teacher to come in and perform a miracle on that scale. That having been said, I am working with the Chinese English teaching staff to identify the areas of greatest need so we can begin to address them together.

Stay tuned for how all this plays out.

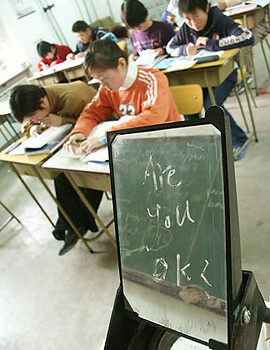

A bored student writes a message on the overhead projector.

A student doodles in class

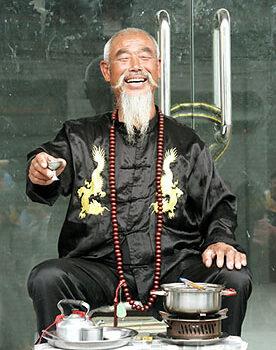

“Happy Man”. I found this guy while wandering around the tourist part of Shanghai. It’s not clear why he was there; but every time someone with a camera walked by, he would pose thusly. He didn’t ask for any money, he just sat there and offered a pose all day long. Hey, it made a great picture!!

A Good Week

One day one of the Chinese teachers who has been tasked with teaching business English asked me to swap subjects, since I have real-world experience with balance sheets and negotiation skills. That was one of the most enjoyable weeks a person can have teaching. The students are advanced in their speaking and reading skills, and can understand the nuances and carry out the complex tasks required of negotiations. For the first exercise, I divided the class into two groups: One group represented Nike (the large American athletic apparel company) and the other was a Chinese clothing manufacturer who wished to become a subcontractor. The situation: Nike has had problems with their current shoe subcontractor in Mexico, and they are looking for a more reliable, cheaper, and higher-quality partner. Before the negotiations started, each side was to elect a president, chief negotiator, CFO, and marketing person (who also kept track of what the competition was doing). I set goals of profitability and sales volume for each side. Then they had to write out what they wanted from the negotiations, what they were willing to live with, and what they were willing to give away in bargaining.

So far these would have made for very boring negotiations (Nike was very big and powerful; the Chinese company was very small and were not in a good negotiating position), and so to level the playing field I went to the Chinese clothing company and told them “Your company has a secret weapon. You have developed a type of rubber that, when put into shoes, can make people jump 2 meters higher. Nobody else has this, and Nike would love to say that people can jump higher with their shoes.” Then I sat back and watched with glee as the kids really got into their role playing.

They made up name cards so they could exchange them during the introduction phase. They made the required “small talk” that their book said was so essential in the pre-negotiating process. The Chinese team tried to change the agenda to get Nike to consider shoes with the secret weapon, but at a substantially higher price. The Nike team did a lot of “chest thumping” and didn’t listen much to what the Chinese team had to say. Both teams had to take breaks from the negotiating table to consult with their team “back home”. At the end of the 3rd session both parties had negotiated a win-win and were quite happy. In the debriefing, I learned that the Chinese team had made three times their assigned goal for profits!!

Then I threw them a curve ball, and was a little taken aback with what the kids did with it. I went to the Nike team and told them “Your new shoes are a hit – they are selling very well, and you have made a LOT of money. Congratulations. But I have a letter here from your business development agent in Russia — (you’re still trying to get your shoes sold in Russia) — and he says your special shoes, with the Nike logo, are already being sold there!!!” The Nike team was furious, and called for an emergency meeting. The resulting conversation went something like this:

“Why do we see our shoes with our logo selling in Russia?”

“We don’t know anything about that.”

“You have been selling our shoes to somebody else!”

“So what? There was nothing in the contract that said we couldn’t.”

“You can’t sell shoes with our logo! We’ll sue!”

“We’re not! We sold them to another distributor. It is they who are using your logo. Your issue is with them, not with us.”

It is clear that these students will quickly develop into slimy business people, a necessary survival skill in China. (I’m so proud.) Right after that exchange I introduced the concept of ‘exclusivity’ as a negotiating point for a contract.

Cultural differences

In preparation for these negotiations, we also had a reading assignment which discussed cultural differences, and how these can sometimes make negotiations very difficult if you’re not aware of them. We all know of the famous ones – burping loudly is taboo in some cultures and a sign that you enjoyed the meal in others; crossing your legs is considered very rude in Saudi Arabia, innocent hand gestures (the “V for Victory” sign, or what Richard Nixon used to do) is considered the ultimate insult in New Zealand. In most countries, if a stranger asks for directions, most people would just take them there. But in America, a native would simply give directions and then walk away. (“How rude!”) This last one can be explained by the different value system Americans have — Americans like to feel independent, and don’t like to feel like they can’t do something for themselves. They also think others must feel the same way, and so would never want to insult another person by assuming that they can’t do something for themselves. So by giving directions and walking away, most Americans feel they have done the right thing by not insulting the person who was lost.

As related to the business world, the following cultural differences caught my attention:

A billion bicycles on an obscure street.

| Westerners see the contract as the end result; which must be airtight and spell out what happens with every conceivable instance. | Easterners see the contract as merely the beginning; it the business relationship that is important. So the contract doesn’t have to be airtight; a good relationship (like a good marriage) means when unexpected things come up, you work it out. |

| Westerners see a request for contract negotiation as going back on your word. If we agree to these changes, how do we know they won’t come back in another 3 months asking to change it again? | Easterners request a renegotiation when unforeseen conditions arise, and (as explained above) is a normal course of business when conditions change. |

| Westerns like to “get down to business”, and separate business with pleasure. | Easterners do not draw a distinction between negotiating and socializing time. |

| Westerners work on “monochronic time” (do only one thing at a time, and interruptions are considered rude) | Many cultures work on “Polychronic time”, where interruptions, phone calls, letters, visits from other clients, etc. are perfectly normal and nothing to get upset about. |

| “In football the object is for the quarterback, also known as the field general, to be on target with his aerial assault, riddling the defense by hitting his receivers with deadly accuracy in spite of the blitz, even if he has to use shotgun. With short bullet passes and long bombs, he marches his troops into enemy territory, balancing this aerial assault with a sustained ground attack that punches holes in the forward wall of the enemy’s defensive line.” | “In baseball, the object is to run home! And to be safe! ‘I hope I’ll be safe at home!'” |

(Sorry… that last one was vintage George Carlin. I get carried away sometimes.)

One final language note: If an English person ever asks you “Won’t you have some tea?”, be prepared to go thirsty. Examined literally, there is no answer you can give that will get you tea. Consider all the possible responses:

“Yes, I won’t have some tea.”

“No, I won’t have some tea.”

This kind of convoluted language usage drives many English students nuts. (And leaves others very thirsty!)

Until next time…

“Yours Truly, Gary Friedman”

October 17, 2003